Nitisha Agrawal goes in search of the Grey Ghost of the Himalayas. Will she find it?

Text by Nitisha Agrawal

In Ladakh, there is a local saying that if you lay your eyes on the grey ghost, as the snow leopard is known, then you are the luckiest person alive. I decided to follow a snow leopard expedition in the month of February with Neerav Singh Yadav, a wildlife conservationist and a friend, whose organisation Scaly Trails runs this expedition in ‘the land of high passes’. Located in Jammu & Kashmir, India, Ladakh is bordered by Tibet, China, Baltistan (Pakistan) and the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh.

The Zanskar River, a tributary of the Indus, courses through Ladakh. (Image credit: Ghaneshwaran Balachandran)

Following these elusive cats that live and prey on heights well above the Alpine tree range (above 3000 m from sea level) in temperatures close to -20 degrees, and braving icy cold winds, with almost zero phone connectivity as well as hours of scanning the overwhelming landscape, is not an easy task. I must add here that the unbelievable landscape of Ladakh and warm hospitality of the Ladakhi Buddhist communities makes it worthwhile. However, it was not only the snow leopard that drew me to this rather difficult expedition – I am no wildlife expert – but also Neerav’s programme. The latter is a model of sustainable tourism with a clear objective of contributing towards the conservation of the endangered big cat. Besides, as part of this expedition, I also found my spirit of adventure temporarily fulfilled.

Little is known or documented about snow leopards, unlike their more famous yellow cousins found on the plains. The reason for this is that the habitat of the snow leopard is spread over an enormous area of almost 1000 sq km, most of it inaccessible. According to officials working at Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust, a local NGO working in the trans-Himalayan regions of Ladakh, Zanskar and Spiti for the conservation of the endangered snow leopard in India, the estimated population of snow leopards in India is anywhere between 200 to 600 (source: www.snowleopard.org). Most snow leopards In India find their home in Ladakh while the rest are found in the Spiti region of Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

A snow leopard scans the arid landscape for its prey. (Image credit: Jigmet Dadul, and courtesy Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust)

Much has been said about the fragility of Ladakh’s ecosystem; in my search of the elusive cat, I stumbled upon an impressive model of responsible and sustainable tourism where residents of remote villages in this region play a pivotal role. Initiated by SLC (Snow Leopard Conservancy) India Trust, the programme is dedicated to the conservation of mountain ecosystems through a community-based approach.

We stayed in the charming village of Saspochey, located in Ladakh’s Leh district at an elevation of 3,712 m above sea level. Little is known about Saspochey as it does not feature among official track routes for snow leopards or even trekking and biking routes that are fast contributing to Ladakh’s increasing number of tourists. It is thanks to Neerav’s experience in leading snow leopard expeditions from the picturesque, quaint village that I got to visit this hidden jewel.

The village of Saspochey (above) and a young resident (below). (Image credit: Ghaneshwaran Balachandran)

Saspochey’s rugged landscape is breathtaking, almost daunting. The incredible adventure lies in taking the untrodden path, not knowing where the day will take you as you wait for that once-in-a-lifetime encounter with the grey ghost. In my brief visit to this region, we scanned the little explored valleys of Karangla and Lang Tang Chang among the usual areas and ridges frequented by snow leopards. We had the good fortune of being guided by the famous father-son duo of Jigmet Dadul and Nawang Gyaltson, pioneer leopard spotters, both of whom play an active role in snow leopard conservation and the Himalayan Homestays project. Jigmet, once a nature trekking guide, has assisted several film crews from various international television channels in making documentaries on the snow leopard and the natural history of Ladakh. In 2014, he was awarded the Carl Zeiss Award for Nature Conservation. Father and son are actively involved in implementing community-based conservation programmes. Gyaltson too is an experienced snow leopard spotter and plays an active role in conducting training programmes for the local village youth to consider snow leopard conservation programmes as a viable career option.

Snow leopard spotter and conservationist Nawang Gyaltson in action. (Image credit: Neerav Singh Yadav)

Gyaltson’s exciting stories about his encounters with ‘shan’ (local name for the snow leopard) makes his life as a snow leopard spotter sound fascinating but the job is a tough one, with a great deal of risk involved. Gyaltson would leave home in the early hours to start scanning territories for these cats while I, on the other hand, would still be warm and comfortable under several locally made yak wool quilts. So many, in fact, that my hosts had to check every morning that I wasn’t actually buried under their weight.

By the time I surfaced, Gyaltson and his team of spotters, would have finished hours of scanning for possible snow leopard pug marks or for the leftover of a kill in the earmarked territory. Every day we would spot at least fifteen to twenty ibexes, wild mountain goats that are the preferred food of the snow leopards. Whenever we spotted a herd of ibexes, our excitement grew with the anticipation of an encounter with the grey ghost. While the latter continued to be elusive, we saw urial or wild sheep, red foxes, golden eagles, and lammergeier or the Himalayan bearded vulture. We also saw what could possibly be the tracks of a wolf pack and our anticipation of a snow leopard sighting increased with every passing hour.

‘Golden hour’ in the Himalayas. (Image credit: Neerav Singh Yadav)

The scanning hours would consume our entire day. The ‘golden hour’ between 5pm to 6pm is considered the most appropriate time for a snow leopard sighting, as this is when they set out to hunt. By then, our bodies were battered by the icy cold winds and tired from treading carefully on slippery ice along undocumented trails; however, our minds were alert for a possible encounter as the evening progressed. Sunset over the Zanskar or Ladakh range of the Himalayas is a sight to behold. There is something immensely surreal, even spiritual about it. But as the evening turned into nightfall without a sighting, we would turn back to our warm homestays looking forward to dinner and heart-warming conversations that awaited us.

I was fortunate to stay at Gyaltson’s wife’s family home during my visit. While the weather outside was harsh, the hospitality of Gyaltson’s family kept me warm and well fed. The grandmother of the house served us khambir (delicious Ladakhi bread) and endless cups of butter tea for breakfast. Before we set out looking for the cats in sub-zero temperatures, she packed us lunch consisting of rotis with jam and butter, and omelettes. I looked forward to my return to the home stay, to Amale (Ladakhi for mother) and her piping hot dishes served around the traditional bukhari (stove) that keeps Ladakhi homes warm.

A Saspochey resident prepares a meal on a traditional stove for her homestay visitor. (Image credit: Ghaneshwaran Balachandran)

Himalayan Homestays, the homestay project, has received recognition for its effectiveness and has been well accepted by the community. It is an award-winning programme, having received the Responsible Tourism Award in 2004, Travel and Leisure Magazine’s Global Vision Award in 2005, the 2008 Geotourism Challenge finalist recognition at National Geographic’s Centre for Sustainable Destinations and Ashoka’s Changemakers award. The homestays programme is ecologically sustainable, economically viable and most importantly, socially responsible. Apart from generating additional income, homestays also help protect the mountain environment. For instance, 10% of the proceeds from the programme go into a village conservation fund which is used by villagers for various activities such as tree plantation, garbage cleaning and maintenance of natural and cultural sites. Since the launch of this programme five years ago, SLC India Trust has seen a change in the mindset of the village community. They are now able to supplement their income through this programme that is also able to mitigate the loss of their livestock to snow leopards. Personally, I believe a similar model can be implemented in other wildlife zones where the human-wildlife conflict leads to both livestock depredation and reduction in the number of predatory wild animals in retaliation.

A traditional Ladakhi village home, part of the Himalayan Homestays programme. (Image credit: Ghaneshwaran Balachandran)

Finally, did I spot the grey ghost, the very reason for my expedition? Unfortunately, I didn’t. Which only makes my desire for the encounter much stronger. However, it is important to note the role played by climate change and disturbances of the ecological equilibrium in the region. There has been warming of the temperatures in the mountains as well as large-scale development of the region to cater to the economic requirements of its people. These, among other reasons, have pushed these shy creatures to expand their home territories, thus making it even more difficult to spot them.

Temperatures are on the rise across the mountains of Central Asia. The Tibetan plateau, home to more than half the remaining snow leopards, is already 3 degrees warmer than it was twenty years ago. These changes impact the entire ecosystem: vegetation, water supplies, animals, and they threaten to make up to a third of the snow leopard’s habitat unusable. Also, an important climatic factor that we witnessed ourselves was scanty snowfall in the season. The mountains looked devoid of glaciers this year, leading to less potable water in the summer months. “While NGOs like SLC are doing a phenomenal job with the help of the local community and foreign aid, it is important that Ladakh’s in-bound tourism is also planned and executed in the right manner,” believes Neerav. Travel curators and facilitators together with responsible governing bodies could take into consideration, he feels, factors like regulating the number of tourists, fee structures and pricing for animal and other adventure expeditions, increasing home stay options, reducing camping trips, and educating tourists on critical issues overall, thus seeding the idea of conservation while travelling.

As for me, I had to be satisfied with the numerous stories of enchanting snow leopard encounters through the photographs and experiences of Neerav and Gyaltson. Enough to plan yet another quest in the great mountain rooftop.

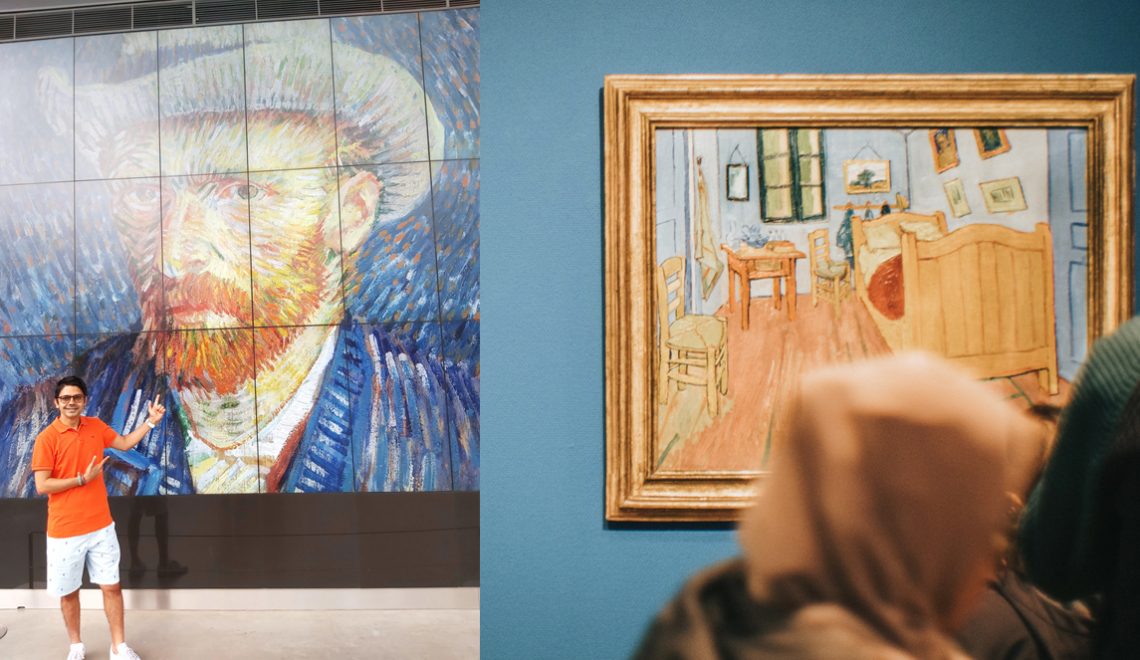

Nitisha Agrawal in Ladakh. (Image credit: Neerav Singh Yadav)

Nitisha Agrawal’s love for the mountains and trekking lured her to a chance interaction with an Australian scientist and she found inspiration to start her own NGO Smokeless Cookstove Foundation under his guidance after quitting her corporate job as Head of Communications with Volkswagen. The Foundation conducts training programmes in the skill of making zero cost smokeless cookstoves for communities living below the poverty line around India. She has studied Sustainable Development and Solutions from Columbia University, Earth Institute, and is currently pursuing a certification programme in Education in Sustainable Development from United Nations, Earth Charter International. She has also started Children of Tribe, an outdoor learning experience and introduction to sustainable solutions for urban children based on the ideology of Nature as a third parent.

Very nice post. Some really valid and useful information here about spotting the snow leopard in ladakh. very well detailed and explained you have a great knowledge. Learned useful things from your post! Many thanks for sharing. Great share I must say!